At a NYC City Council General Welfare Committee hearing on racial disparities in child welfare, parents – including Rise’s Jeanette Vega and Imani Worthy – and advocates citywide testified about urgent adjustments and broad shifts to reduce the reach and harm of child welfare. This is Rise’s written testimony.

Thank you for holding this hearing to focus on racial disparities. Racism is evident in the design, practice and impact of child welfare in New York City. While the child welfare system claims to support NYC families, it causes trauma, stress and shame to parents and children.

The parents that we work with are Black and brown parents living in low income communities. These are parents who are guilty of poverty. They are parents who reach out for help and get a hotline call and investigation from the people they trust during hard times in their families.

Disparities That Are Visible Every Day

For parents simply walking into Family Court, it is obvious that this is a system that almost entirely impacts Black and brown families and communities. As Rise Parent Leader Imani Worthy has written:

“Going to family court is like the feeling of marching to the guillotine. You’re ashamed and your mistakes are put out to the public.

“While in the courthouse, I couldn’t help but notice a barrier when you enter. Lawyers, judges, clerks, ACS caseworkers, and staff walk in on one side. On the side where the employees were walking in, I noticed a lot of Caucasian people entering.

“The other side is for the general public. The general public had so many black and brown faces.”

Read Imani’s testimony

For Black and brown parents, the roots of the system’s disproportionate impact on low-income families of color are also obvious: under-investment in supports for low-income families.

Support That Comes with Strings Attached

Too often, the only supports available to low-income families come with strings attached: the strings of surveillance, of loss of control, of punishment. Parents who need help with school challenges, a winter coat or box of food know that every request for assistance can put their families at risk of a hotline call, an investigation and even family separation.

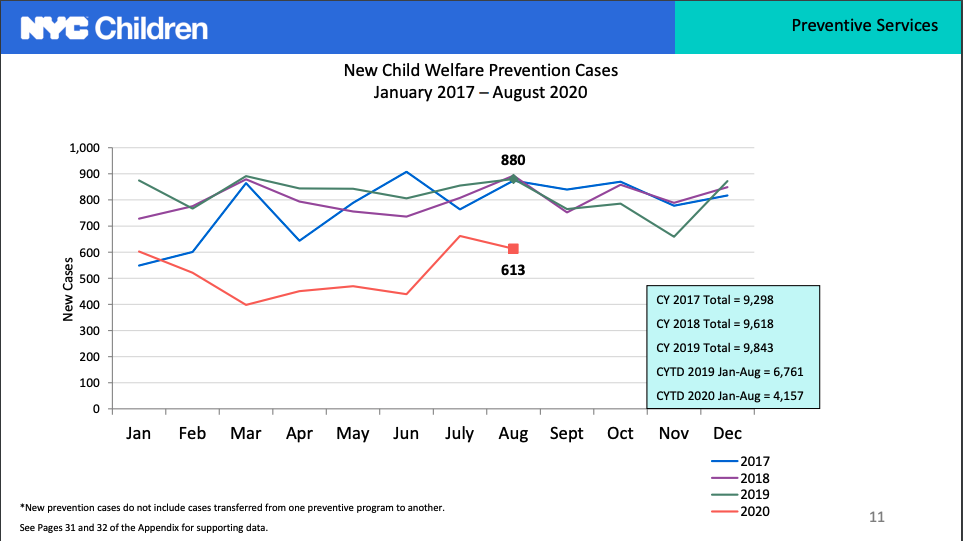

Parents would rather hide their struggles that reach out to an agency that is connected to ACS. You can see it in the numbers. ACS’ most recent data shows that families did not utilize ACS-funded Preventive services during the pandemic, even though these were highly stressful months for families.

Families needed and still need basic resources and support—cleaning supplies for their homes, help with technology, support to de-escalate tensions, especially as parents are teachers now for their children. But the system is known for punishing families for their struggles instead of providing support.

This is inequity–white families and more well-off families do not have to carry the fear that asking for help will destroy their families.

Achieving racial equity means reducing stress on Black and brown families and removing barriers to resolving family challenges without fear.

When we continue to structure child welfare and family support as they are now, we continue a system that is widely recognized as racist in design and impact.

Despite the best intentions to protect the well-being of children that people may have working within this system, the child welfare system reproduces cycles of harm and trauma that impact Black and brown low income communities. This is unacceptable and must end.

Policing of Families in Black and Brown Communities

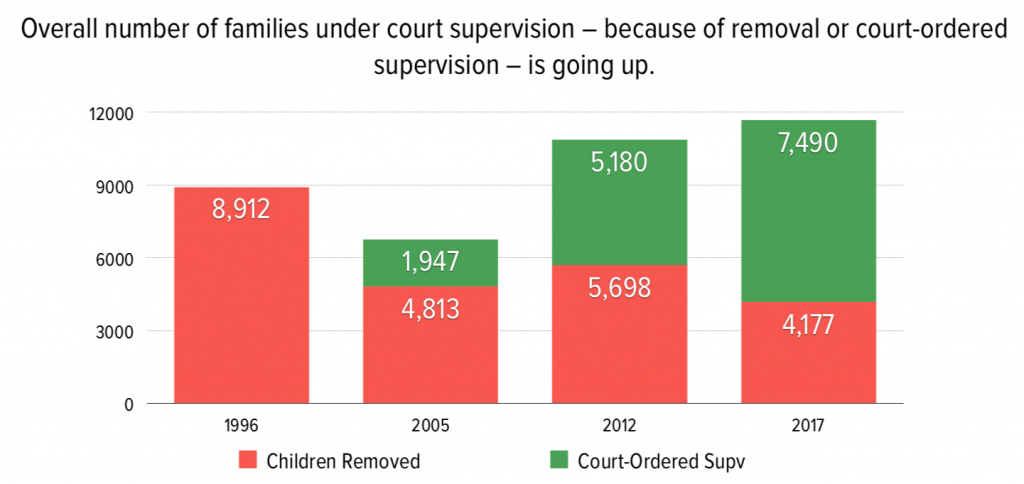

We want to call your attention especially to rising rates of family surveillance in New York City. City Council frequently hears from ACS that, in New York City, the number of children in foster care has dropped dramatically in the past 20 years. This is a critical success. However, it’s time for ACS to acknowledge another statistical fact: ACS’ threatening presence in poor communities of color has grown.

Investigations have increased from 54,039 in 2013 to 59,166 in 2018 and are concentrated in poor communities of color. In Hunts Point in 2017, 10% of families were investigated. Between 2010-2014, nearly one in three families in Brownsville were subjected to an investigation, according to ACS.

In addition, the city has aggressively increased use of invasive “court-ordered supervision” to monitor families. While 5,000 families per year were typically under court monitoring until recently, that number has doubled. In 2017, more than 10,000 families had to report to a judge about how they were addressing family challenges, under constant threat of removal.

In our communities, an accident, a conflict with a child’s school, or one overheated moment in our family life can turn into a knock on the door.

Child welfare involvement has climbed even as the number of children living in poverty in NYC has dropped, to 23.8% in 2018 from 30.1% in 2011-2015

Living in Fear

At Rise, we hear constantly that families are fearful of the support ACS claims to provide. I’m sure you’re hearing the same from your black and brown constituents.

Lou endured seven investigations, even while enrolled in a family support program. She wrote:

“I made it part of my daily routine to take pictures of my kids before taking them to daycare and school so that I would have proof that my children were fine before they left my home,” she wrote. “That’s probably not something many parents would even think of doing, but for a parent like me, it just makes sense.”

Can you imagine living in this daily fear?

Cynthia wrote:

“I followed all their instructions. I didn’t go to work once a week for months in order to take my daughter to a psychologist who was an hour away by public transportation. I left my job early every two weeks to receive CPS investigators at my home. My daughter, who was only 3, was so nervous being interrogated by strangers so many times that she started behaving irregularly. And, as the investigation dragged on, I was so nervous at work that I couldn’t concentrate. Plus, my boss was losing patience with my increasing absences. Eventually, I lost my job.”

Surveillance hurts families and weakens communities. We are scared to talk to our doctors or our children’s teachers. These people are supposed to be our helpers, but because of over-reporting, we see them as people who can harm us. That makes children more vulnerable. Parents who are struggling hide what they’re going through, and struggles can become crises.

Parents raising children under the double burden of economic hardship and racism should not have to live with unprecedented scrutiny of our parenting. Families under stress need opportunities to decompress. We need safe places for our children. We need opportunities to develop strong relationships with other parents. We need outlets from isolation and stress.

Steps to Reduce Family Policing

In New York City, we know stop-and-frisk didn’t improve safety, and neither does over-reporting and monitoring of families. It’s time for ACS to set a new goal—to strengthen families without surveillance.

Two major shifts in investment can immediately reduce unnecessary surveillance:

- Greater investment of city dollars in support strategies that help families find assistance and support without child welfare involvement, such as community-based parent advocates and parent support groups, school guidance counselors with capacity to assist families, or increased advocates for parents navigating children’s behavioral and educational needs.

- Creation of a family support hotline that parents can call for confidential information about community-based supports, with parents/parent advocates designing the protocols and assistance provided.

City Council can support a goal of reducing family policing by holding ACS accountable to working with other city agencies and the state Office of Children and Family Services to reduce unnecessary hotline calls and investigations, and by making public essential data so that advocates and the media can hold ACS accountable as well.

This includes:

- ACS must provide data on the results of reports made by mandated reporters. That should include the number of substantiated and unsubstantiated reports made by all mandated reporters, as well as breaking out that data by type of reporter (school or hospital personnel, for instance), and by the child/family’s race and community district.

- ACS must work with other city agencies including the Department of Education, Health and Hospitals Corporation, and Department of Homeless Services to aggressively target schools, hospitals, shelters and other institutions that disproportionately and erroneously report families. Past efforts to determine individual schools that have a pattern of overreporting, to clarify the mandated reporter role to those school personnel, and to connect those schools to local community organizations that can support families in distress have made a difference. Not only do these efforts protect families from intrusive and stressful investigations, but they save money now spent on investigations that can be invested in strengthening community supports. ACS must report publicly on these efforts and results.

- ACS must work with OCFS and city agencies to train mandated reporters to understand not only the need for reporting but the seriousness of reporting a family to the hotline when issues could be dealt with by supporting the family through a school’s guidance department, PTA, Beacon Program (which are usually underutilized in referrals from school personnel but serving families referred by CPS investigators), or through community organizations trusted by parents. This training should include parents who have experienced unnecessary and harmful hotline calls. City Council must require ACS to report its efforts to reduce unnecessary calls and route families to supportive resources.

In addition, City Council must advance legislation and funding to protect families that are investigated. This include:

- Expansion of free legal support to parents at risk of or facing an investigation.

- Creation of a “Miranda”-type warning so that parents know their most basic rights at the beginning of an investigation, including the right to seek legal counsel, and provision of written information in multiple languages explaining parents’ rights and resources.

Target Conditions, Not Families

More broadly, City Council must use its political will to support a culture shift in how NYC support vulnerable families. In our communities, schools, parks, sports and arts programs for children, mental health supports for families, affordable and safe housing, and crisis services are often inaccessible or low quality. Yet rather than target community conditions, the child welfare system targets individual families.

It’s critical to align city spending with families’ real needs and move dollars into community supports that are not connected to ACS.

ACS has recently expanded programs intended to approach families more compassionately. You might think this is a reason to applaud, but we ask the City Council to think differently. These programs still represent an investment in ACS, not an investment in community-led and community-accountable organizations that parents trust. These programs have been created with good intentions but a fatal flaw—their affiliation with an agency that strikes fear in families’ hearts.

These ACS programs intended to offer a softer landing to families include FAR (Family Assessment Response), now called CARES, which replaces a full investigation for low-risk families, and the Family Enrichment Centers, which offer support without monitoring. However, parents do not want to receive supports or resources through ACS-affiliated programs. Instead of a CARES investigation, we need to work to eliminate unnecessary investigations and create a support hotline that families feel safe calling when they need help. Instead of enrichment centers run by ACS-affiliated social service agencies, we need to shift that funding to expand the capacity of trusted community organizations to welcome and support parents under stress.

We recommend that, as City Council members, you ask your constituents about the organizations they trust in a family crisis — and learn the barriers and opportunities to build up those organizations. Contracts through DYCD or even HRA, or through an expanded Children’s Cabinet or newly created Mayor’s Office on Families, can support the development of family-serving organizations independent of ACS that can support families without making them “known to the system.”

We already know that ACS-funded prevention programs have extremely low rates of voluntary utilization. Surely, city dollars can be better spent on inherently trusted and committed community-led organizations.

Invest in Communities, Not ACS

To be clear, we are asking City Council to commit to DEFUND ACS and FUND communities.

We’re sure the Council has heard and seen and heard parents and advocates calling for abolition of the child welfare system. That is because we know that the current child welfare system does not work and simply calling for reform of the system will not work either.

We are seeking to create new ways address the pain, fear and hurt people are carrying, from a place of compassion, care and humanity. We can look to the ways prison and police abolition organizations are creating credible messenger interventions and community healing outside of system. Those point the way to abolition of the child welfare system. As Dorothy Roberts says, “Abolishing policing also means abolishing family regulation.” And Ruth Wilson Gilmore reminds us “Abolition requires that we change one thing: everything.”

To truly support low-income families of color, New York City must reduce the footprint of ACS and channel funding to trusted community-based organizations that can assist families, prevent and address harm without the terror of system involvement, and support community healing so that all families in NYC have the opportunity to thrive.