By Keyna Franklin, Assistant Editor and Shakira Paige, Peer Trainer

Parents need resources to support LGBTQ children and youth in being affirmed, safe and celebrated in their homes, schools and communities. In our report, An Unavoidable System, Rise recommends expanding access to community-based programs that center the needs of families with LGBTQ children—without family policing system involvement.

Here, Rise talks with Caitlin Ryan, Director of the Family Acceptance Project at the Marian Wright Edelman Institute at San Francisco State University in California, and Angela Weeks, Director of the National SOGIE Center at University of Maryland School of Social Work’s Institute for Innovation and Implementation. They discuss their new national website, the need to center parents and families in caring for LGBTQ youth, the impact of family’s accepting and rejecting behaviors on LGBTQ youth, examples of affirming behaviors by parents and how community-led resources can prevent family policing system involvement.

Note: We invite you to review a few relevant terms and acronyms before reading this article. While we frequently use the term ‘parents’ in this article, we recognize that a caregiver may be a grandparent, older sibling or someone other than a parent.

Q: Please tell us about your work to develop resources for families of LGBTQ children and youth.

Ryan: I’m lesbian-identified and have worked in LGBTQ health and mental health for 46 years. One of the biggest challenges historically—and today—is that families have been excluded from the care of their LGBTQ children. Instead of support, there has been anger and blame toward parents. Even therapists were not including families in the care of their LGBTQ children. This prejudice has persisted—especially with parents who have children in the foster care system. There’s a lack of efforts to include parents and address issues from the perspective of their cultural and social worlds.

I started this project to develop an online resource for families based on work I did in the South, including with many African American families, in the early 1980s during the AIDS epidemic. I was deeply struck by the desire of many parents to do whatever they could to help their gay and bisexual adult children—it was so different from the prejudice many people had about families.

Years later, I started The Family Acceptance Project and began to do research about LGBTQ youth and families, looking at the role of culture, religion, values and beliefs. We developed the first evidence-based family support model to decrease risk and increase well-being in the context of the family’s culture and faith traditions. We want parents to know how to protect their children—and that they don’t have to choose between their child and their culture or faith.

The Family Acceptance Project and the SOGIE Center developed this new national online resource so that LGBTQ youth and their families can access affirming, culturally-grounded and faith-based resources that provide accurate information and increase family support.

Weeks: The Institute for Innovation and Implementation got a grant from the Children’s Bureau to develop and evaluate programs across the country for LGBTQ youth in the foster system and their families. Our goal was to improve well-being outcomes for LGBTQ youth in the foster system, increase stability and reunify families sooner. We partnered with The Family Acceptance Project because we want to think critically about how resources can be offered in the ways families need so they can show up for their children in the ways they want.

Q. How did you develop the new website? What community-based resources are available for families of LGBTQ youth?

Ryan: We searched far and wide to identify affirming culture- and faith-based resources across the United States. We included resources with affirming cultural events, activities and educational support groups that a parent could call and say, “My child is fourteen (or whatever age). Can you help me understand how to deal with these issues within our faith and cultural beliefs?”

In all our work, LGBTQ young people and families were at the table, participating in doing research, developing our family support model and resources and providing feedback. Cultural advisors from many different racial and ethnic groups provided guidance on the resources, posters and social media graphics we developed. We work in multiple languages and know there are different concepts and ways of talking about identities across languages.

Many young people are fearful about coming out to their parents because they’re afraid of being rejected—but keeping secrets about our identities is harmful and contributes to serious physical and mental health risks. Often, youth don’t have a place to send their parents where they can get help in their own language or from their faith tradition, cultural background or racial values. We wanted a safe, affirming place that a young person could tell a parent to go to for resources and support and where families and youth could go together.

The new website has a national map that includes LGBTQ community centers, LGBTQ-affirming youth organizations and services, gender clinics and services for parents of LGBTQ children and youth. We also list affirming faith-based and culture-based resources.

Q. Why is it important to center parents and families?

Weeks: There’s been a lack of conversation around families, especially in systems like the child welfare system. We can see that in the way systems have been built and resources have been developed and delivered. There are fewer resources for families around understanding LGBTQ identities. There’s often a lot of effort put into developing programs for young people to have skills to live on their own—as opposed to ensuring that families have what they need to be there for their young people.

Ryan: There are many barriers to LGBTQ young people living happy, healthy lives, including misinformation in the family and other systems. Parents don’t have access to accurate information about sexual orientation and gender identity—or it isn’t presented in relevant ways. Our research found that parents learning to advocate for their LGBTQ children in different systems is critical for protecting against risk, promoting children’s well-being and strengthening the family. Our shared mission is to center this work in the family and engage everyone as partners in reducing children’s risk and increasing connectedness.

Q. What does research show about the impact of families’ accepting or rejecting behaviors?

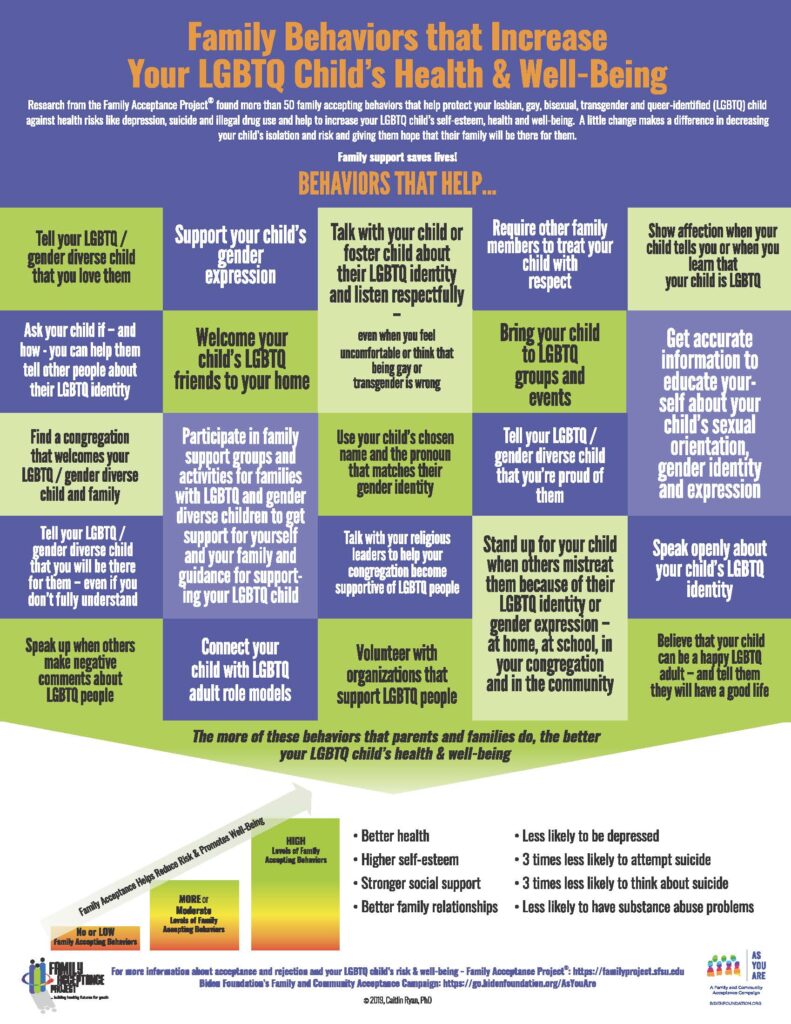

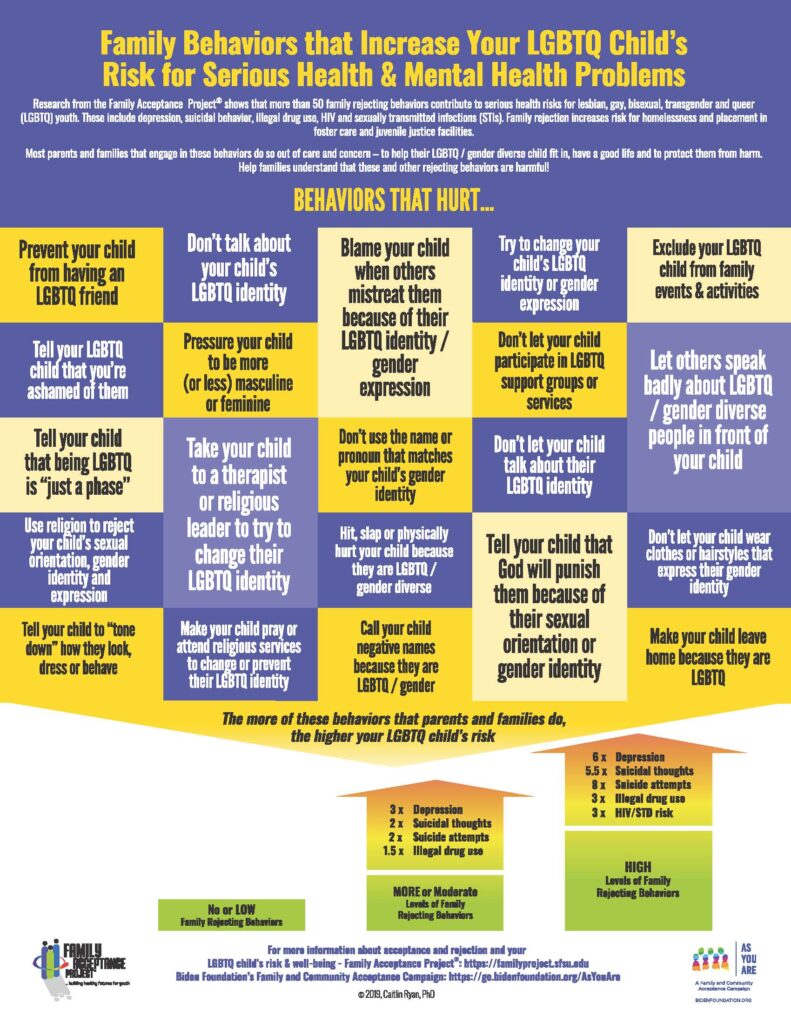

Ryan: Our research measured over 100 specific ways that parents and caregivers respond to their LGBTQ children. This included everything from affirming behaviors (e.g., finding a positive role model, talking with religious leaders about welcoming LGBTQ people) to rejecting behaviors (e.g., not letting them have an LGBTQ friend or using slurs to talk about their LGBTQ identity).

Our research shows that affirming family behaviors increase support and protect against risk— and family rejection contributes to serious health risks. The more rejecting behaviors by families, the higher the level of risk, and the more accepting behaviors by families, the lower the level of risk. Accepting behaviors promote children’s self-esteem, overall health and well-being and family connectedness.

With high levels of family rejection during adolescence, LGBTQ young adults are more than eight times as likely to attempt suicide, almost six times as likely to report high levels of clinical depression and more than three times as likely to use illegal drugs and be at high risk for sexually transmitted infections and HIV. When LGBTQ young people experience high levels of family rejection, as young adults they are more likely to be in relationships where they’re abused. In the long term, people rejected by their parents have much lower income and educational levels.

This information is vital for parents, because they can understand that they’re shaping how their child sees themselves and their child’s whole life ahead of them. Our work focuses on caregivers’ behaviors and underlying values. Typically, they want their children to be happy and healthy. They want to be good parents and keep their family together. They want their children to succeed and, of course, health and well-being are at the core of the hopes that caregivers have for their children, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity. We’ve been able to show that when parents have accurate, culturally-relevant information, they change their behaviors to support their LGBTQ children.

Q. What are examples of behaviors by parents that affirm and support LGBTQ children and teens?

Ryan: A simple affirming behavior is to sit down with your child and listen respectfully about their experience and their LGBTQ identity. This does not require a parent who is struggling to accept a behavior or an identity that they think is wrong, but is a way they can show their child, “I care about you. I’m concerned about you. I’m here for you.” They could say, “I don’t know much about this, but we’ll learn together.”

It is important to learn about sexual orientation and gender identity, not only to understand your child but also so you can communicate to other people about why it is essential that you support your child. You can affirm your child by requiring that all family members treat your child with respect because they’re a member of the family, or, for example, if you’re religious, because they are a child of God. In the community, if other people mistreat, disrespect or bully your child, whether at the grocery store, at school or in your congregation—stand up for your child by speaking out. Show your child, “I have your back. I may not understand this, I may be struggling, but I’m there for you no matter what.”

We teach parents about the powerful role of advocacy—and that it’s not just advocating for your child one-on-one, but in the family system, in your cultural world and in their school. Part of parenting is teaching your child self-care and how to care for themselves when they’re an adult. We can begin to do that now by teaching them to deal with adversity or challenges they may face, which may include people mistreating them.

You can take your child to, and/or volunteer at, LGBTQ community events and activities. (Our resources highlight Black Pride, Latinx Pride, a Two-Spirit Pow Wow and Lunar New Year or Diwali, which is a South Asian Festival of Light.) By affirming your child in front of others, you can support your child and help to change attitudes other people may have. Additional affirming behaviors include welcoming your child’s partner and/or LGBTQ friends, validating your child’s clothing and hairstyles and telling your child you’re proud of who they are.

Weeks: One of my favorites is expressing affection—so if you would always tell your child, “I love you” before they went to school, don’t stop doing that when they come out. Continue to tell them you love them. If you always gave them a hug before they went to bed, continue giving them that hug. It’s so important that they don’t feel like your regular affectionate behaviors towards them have changed. Even if a caregiver or family member is struggling, those are easy go-tos because at the core, they still deeply love their child and want them to be okay.

Q. What do you want parents who are starting to learn about their child’s sexual orientation or gender identity to know?

Weeks: You play an important role in that young person’s life—your love and support matters. There are ways to show your love for your child without having to change your belief system or values. Changing things that are core to your identity is not essential to continue to show love.

Ryan: It’s important to understand what sexual orientation and gender identity are, that it’s not something that your child is doing to be disrespectful, rebel or reject your culture, beliefs or faith traditions. It is a normal part of human development—we all have a sexual orientation and gender identity. This is part of who they are, just like their personality, abilities, how they move and their tone of voice. They may share it at different times or places in their lives, perhaps when they feel comfortable or safe.

Now that images of LGBTQ people are in the media and online and talked about at the dinner table and in congregations, kids are learning about sexual orientation and gender identity and coming out at earlier ages. Sometimes they hear that coming out would not be safe. It is important to understand that you cannot change who your child is—and if you try to do so, you can potentially teach your child to hate themselves.

Q. What should parents know about when children develop a sense of their sexual orientation and gender identity?

Ryan: In my work over the last 15 years, I’ve seen kids come out as gay at age six or seven. Many people don’t expect that because they think that being gay is only about sex—but it is about identity and emotional connectedness. We’ve also seen many children identify as transgender in early childhood. Research suggests that around age three, children have a sense of gender identity and can recognize different genders and forms of gender expression.

Q. What does data show about the experiences of LGBTQ youth in the foster system?

Weeks: About 20-30% of youth in the foster system identify as LGBTQ, which is two to three times the general population. Most of those LGBTQ young people in the system are youth from families of color. Across studies, LGBTQ youth in the foster system report similar outcomes. They move around more within the system. One reason for this could be foster parents who are uncomfortable with their sexual orientation or gender identity. LGBTQ youth are placed in residential facilities at twice the rate of their non-LGBTQ peers. They report being fearful about telling their social workers about their identities. They’re concerned that if they tell anyone about their LGBTQ identity, they could be forced to move or unable to reunify with their families. LGBTQ young people report poor treatment by the system at higher rates and are much more likely to be hospitalized for both physical and emotional reasons. Overall, they experience a lot of stigma and discrimination. This data provides a snapshot of their experiences in the system and issues that may contribute to their lower rates of reunification.

Q. What does research show about support for parents of LGBTQ children and youth involved with the family policing system?

Ryan: In 2015, we did a project in Wayne County, Michigan, working with families referred through child welfare system investigations. Using the Family Acceptance Project’s approach, we helped parents decrease rejecting behaviors that were contributing to conflict and to the reasons for the investigations. All families who completed the program became more supportive and affirming. None of their children were removed as of a six or twelve month follow-up.

In California, we developed our family support model by working with families who were system involved, had an investigation or were remanded by the court to work with us to prevent removal. We were able to help families engage in the behaviors needed to keep their families together. The proof of the effectiveness of information and support is all the families who changed behaviors they learned were harmful to their child.

Historically, funding has not been available for prevention—it was only available for services after your child was removed. That makes no sense. The whole family suffers when a child is removed. Why wait until the family is really struggling? Why aren’t programs available in congregations, community centers and public housing to provide education about family support, sexual orientation and gender identity? This is vital for child and family well-being.

Q: Why is it important to have community-based resources for LGBTQ families led by and for Black, Latinx and Indigenous people and other people of color?

Weeks: Communities know best what their community needs. Families of particular races, backgrounds and cultures are able to provide more appropriate services and resources to the communities they represent. For example, a Black parent might go to a clinic with no Black clinicians. Maybe they want to talk about their young person’s sexual orientation, but they experience racial trauma because the clinician is racist or doesn’t understand the impact of not only sexual orientation, but race and perhaps the importance of the family’s religious community. It is important that people serving communities, families and youth are comfortable talking about all aspects of young peoples’ and families’ lives, including sexual orientation, gender identity, race, disabilities and immigration status.

A lot of distrust for LGBTQ services has been because they haven’t been culturally specific or informed. Many programs focused on sexual orientation and gender identity were developed without people of color and without consulting families. For systems and community services to better respond to families’ needs, we need frameworks that don’t separate SOGIE and race, but instead look wholly at all identities that impact young people and families. We need more programs that center multiple identities, including race, culture, language and immigration status. By partnering with youth and families in developing programs, community-led organizations can build rapport, community trust and culturally-specific materials.

Q. How can information and community-based resources prevent family policing system involvement and help parents support their LGBTQ-identifying children?

Weeks: We need more resources and programs for families that are integrated into our daily lives, perhaps administered by schools, health care providers and community centers. There are many programs and resources families can access once they are engaged in the child welfare system, but people should have access to what they need without system involvement. We need to shift so that people can access support in their neighborhoods earlier on, before any family crises. It’s not just LGBTQ programs—there are many programs that should be available to communities that you can’t get unless you are system involved. These services should be free, accessible and available to people in their neighborhoods when they need them.

Ryan: We desperately need systems of care to understand that parents are vital to the well-being and survival of their LGBTQ children. Almost 10 years ago, I wrote Generating a Revolution, a paper calling for pediatricians to teach parents about sexual orientation and gender identity when children are little, as a normative part of education about child development. Information related to sexual orientation and gender identity should be part of routine care for every child and family member—but it is not.

Teaching families how to take care of their children when they’re little can prevent family disruptions, child removals and a range of negative physical and mental health risks. We have years of research on sexual orientation and gender identity and low-cost, culturally-appropriate ways to teach families affirming behaviors—let’s make that available. We have evidence that when families have information and support, they can adapt and their children thrive.

Terms and Acronyms

- The acronym LGBTQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning.

- The acronym SOGIE stands for sexual orientation and gender identity and expression.

- Sexual orientation is an enduring emotional, romantic, sexual or affectional attraction or non-attraction to other people. Sexual orientation can be fluid and people use a variety of labels to describe their sexual orientation.

- Gender identity refers to a person’s internal, personal sense of their gender. Gender identity is best represented as a spectrum and an individual may move around this spectrum. Some terms that are associated with this spectrum are man, woman, gender fluid, genderqueer, trans, transgender and Two-Spirit, although these are not the only terms. Some individuals may identify as both man and woman, neither man nor woman, or non-binary. One’s gender identity may or may not correspond with the sex and gender assigned at birth.

>> See Rise’s list of resources for LGBTQ parents and parents of LGBTQ children and youth.

>> The Family Acceptance Project developed posters to help decrease family rejection and health risks and increase family support and well-being for LGBTQ youth. Their Poster Guidance provides background information on the research behind the posters and gives suggestions for how to use them. The posters and guidance are available in 11 language and cultural versions to download directly from their website.