Nine out of 10 foster care agencies nationwide say it’s tough to find and keep caseworkers that are qualified, and a recent study in New York City, 4 out of every 10 caseworkers left the job in the first year they were hired.

Nine out of 10 foster care agencies nationwide say it’s tough to find and keep caseworkers that are qualified, and a recent study in New York City, 4 out of every 10 caseworkers left the job in the first year they were hired.

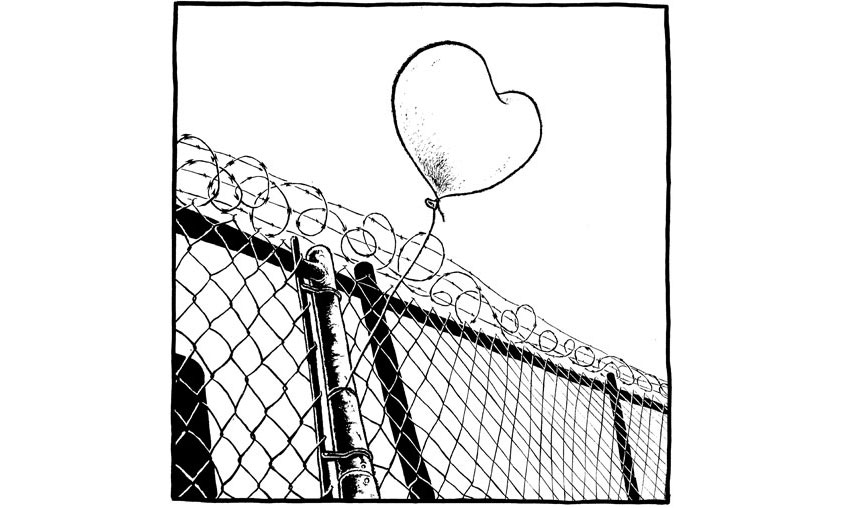

If you’re a parent who hasn’t had a good relationship with a caseworker, you may say, “Who cares if caseworkers stay or go?” But having many different caseworkers, or having an inexperienced caseworker, can impact your case.

In 2011, child welfare professionals Barry Chaffkin and Viviane deMilly created Children’s Corps in New York City because they believed they could hire and train caseworkers who wouldn’t quit. They sent those caseworkers out to work at agencies across the city. At the end of one year, only 1 out of 10 left their job.

Here Chaffkin explains the Children’s Corps approach to hiring and supporting caseworkers.

Q: Why do caseworkers leave their jobs?

A: Caseworkers have too much work, too much stress. Workers are doing everything: visiting parents, visiting children, visiting foster homes, going to court, doing paperwork, setting up services and sometimes taking parents to services.

Also, when you’re a caseworker, you can’t help but be affected by the work you do. Most cases are not abuse. But some are. As a worker, how do you feel when you go home at the end of the day after you’ve seen a 5-year-old with cigarette burns? It’s very, very troubling that we don’t think more about the effects of the work on people.

Workers feel like they don’t have enough support, training or supervision. New York City is trying to change that with its Workforce Institute. But in most places, the amount of training workers get before they start is none.

We know that for families, it can be very difficult to adjust to a new caseworker. Repeating your story over and over can be a form of trauma for a parent. Plus, it takes time for workers to know a family. They have to know the family history. They have to learn all the dynamics. When another worker comes, it can have a major effect on that family’s ability to achieve permanency.

Q: How does Children Corps hire differently?

A: Studies show that certain qualities are important for caseworkers to be effective and to stay on the job, and we try to hire workers with those qualities. Our thinking is: You can hire an elephant and try to teach it to climb a tree, or you can hire a squirrel.

Children’s Corps puts out ads on 190 college campuses across the country. Then we do something called “behaviorally based interviewing” that a lot of major companies use.

We are looking for people who are nonjudgmental, empathetic and understanding. We want people who are open to learning—including learning from parents. We want people who understand that the stress of poverty may make parents do things that are less than ideal, and that sometimes what brings families into the system is an isolated incident, and then people get stuck in the system.

We want people who are flexible, adaptable and resilient, so they don’t quit the first time they are yelled at in court. We actually try to talk people out of the job. We are honest about how hard the work is.

We also make sure the people we hire understand how much of the job is about working with parents. Some workers think they will be working with kids all day. But you’re not a camp counselor. You can’t help children if you can’t help Mom and Dad.

We ask questions to find out what applicants actually did in situations they faced in the past. We also give applicants scenarios. Because we’re in the digital age, we show a video clip of Maggie Gyllenhaal in the movie Sherrybaby. In the movie, she’s been in prison and she wants her child back. Her brother and wife are the kinship parents. They raised the baby from 0 to 3.

We ask applicants to respond to this scenario. The right answer is not always one thing or another. Sometimes the right answer is, “I need more information.” Sometimes, the right answer is, “I don’t know.” We are not looking for a right answer, but to understand how people make critical decisions.

Q: How do you train new caseworkers?

A: Once we hire our caseworkers, we place them at child welfare agencies. But first we give them four weeks of training on thinking openly and creatively, on engaging people, on how to get people the help they need. We also have panels of children, parents and foster parents to speak about what it’s like to be part of the system.

After workers start in the field, we have monthly meetings for caseworkers to share experiences with each other. Sometimes people just need to vent, and get some relief from the stress in their heads. Workers also get a professional mentor.

Workers also have the 40-50 other workers they start with. They go out as small groups to brunch on Sunday, and they can talk to each other. They have a Facebook group, and they can share resources that way. If one caseworker needs a babysitter for a Spanish speaking mom in the nighttime, that’s not easy to find. But if you say that in the group, out of 50 people there may be someone who says, “Try this.”

Q: It sounds like you hire people straight out of college, but many parents are skeptical of young caseworkers or caseworkers that have no children. How do you think hiring young people impacts the quality of work?

A: We do hire some older people and some people who have children, although the bulk are in their early and mid-20s. But we also don’t believe workers have to have all the answers. We’re not looking for people who have taken a college psychology class and think they are parenting experts. What we’re looking for are workers who have humility, who can support and help parents, and who have the ability to learn from parents.

Q: What are the biggest obstacles to improving casework practice in all child welfare agencies? Why do you think it’s important to do it?

A: Some places have civil service exams that determine who can be hired, which makes the whole process even more complicated. But even when that’s not the case, agencies generally don’t have time to do the in-depth interviewing that we can do. It’s usually the supervisor who interviews a person. But supervisors are stressed out doing their day-to-day job, and then they have to squeeze in an interview. So the ability of agencies to do a really thorough hiring process is limited.

Hiring the right people is hard to do and it takes resources. But I think if we don’t put our resources into the frontlines of this work, we’re making a huge mistake. Workers are the ones really involved with the families and they are the ones that have the biggest impact. When we hire the right workers, and train them in the right way, then we will have better outcomes for children and families.